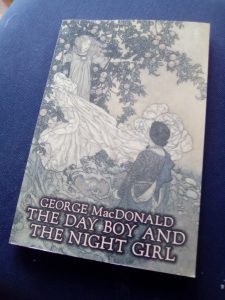

I read the classic tale The Day Boy and the Night Girl recently, having remembered it from an old Andrew Lang book of Fairy Tales I read as a child. As a child I worked my way through my local library’s collection of these fairytale books in many colours – violet, yellow, blue, scarlet – as my grandmother did in her own childhood in the 1930s. This is the so-called original of the story, which I found and bought as part of my quest to ground myself in fantasy from start to now – and fantasy from all over the world.

The tale would not be written this way now – but shows surprising sensitivity over male/ female roles. The girl has no concept of a creature such as a boy, meaning I can immediately imagine this as an asexual fairy tale; or a lesbian one. The witch is truly evil, though it’s not clear why she carries out this odd experiment to keep the girl always in darkness and the boy always in light. The result is the pair being mutually dependent on each other, which is logical enough, and in love, which seems less so, given how traumatised they are. But still. Plenty to chew on here.

MacDonald’s versions is itself a reimagining of an old tale. Nothing new under the sun, or moon. It was an enjoyable read and set me wondering: What are the elements of a classic fantasy tale? How can you give your story that timeless, old-school feel? From the tale I established these elements:

Make it an allegory. Darkness versus light is the oldest tale in history. Eng Lit professors have made a living off unpicking heavily-disguised versions of this in every form – but what if you saved them the trouble, and just make your tale about Dark versus Light? The Day Boy and the Night Girl does this to extremes. So does the BBC radio comedy, Elvenquest. Its villain is the unpleasant and ineffectual Lord Darkness. You get the idea. (Check out Elvenquest. It’s awesome. Guaranteed spit-out-your-coffee funny.)

What other allegories could you create? Well, aside from that biggie, you could do love versus hate, pain versus pleasure… and so on.

Keep the worldbuilding simple. Never mind giving us the centuries-long history of how each person came to be in their current position. Cut to the chase: there was a world in which people were birds. Or whatever. The reader will fill in the gaps. The Day Boy and the Night Girl just says there was a witch, and continues from there. We all know what a witch is, right. So go.

Use the accepted tropes of the fairy tale. In European culture, this involves castle, flowing dresses, knights, dragons. In Chinese culture or Indian culture, this is different. Set up your story with a firm setting and then you needn’t spend ages explaining it all to us. Overly-built worlds detract from the clean, classic feel.

Create mostly two-dimensional characters. Aha, controversy. But a fairytale character does not need a huge backstory or character arc. Mischievous Jack and his Seven League Boots did not learn a huge life lesson, nor did he change much as a person after he killed various similar-seeming ogres. A maiden’s job in a classic tale is usually to stand for something, such as virtue, not to discover herself and start a revolution. It may be her job to marry the correct person from a set of three (and their job is to represent the various traits she must choose between). So while your characters may have characteristics, these might be limited to their hair colour, (see my page on the pitfalls of character trait quizzes) strength or lack of it, and their name. This is a great chance to have fun. Be twelve again. Write the fairytale, do not worry about making every person a complete and rounded character. You’ll be amazed how this speeds things up.

Do have a good story shape. Fairy tales can get away with ‘and then they got married’ but this is harder to pull off in the modern world. Rereading a lot of fairy tales, they do not have proper endings. Jack chopped down the beanstalk and … kept the gold. That was it. The beanstalk story is basically a heist.

Hansel and Gretel is better – they are victims, then they trick their captor, then they defeat her. Much more satisfying. I read one recently where the prince had to choose between three princesses. His dad gives him advice. Give each girl cheese and see how she eats it, then choose. Yes folks, you can discover your life partner by observing the way they cut cheese. Then the prince chose the girl, the end. This is mildly entertaining but I wouldn’t say it’s great as a story.

Ogres, cats, porridge, elves, wolves, goats, beanstalks, lamps, seven league boots. Fairytales have more going on than who to marry.

Make sure there’s a big problem – we’ve been abandoned by our parents in a forest – then a moment of decision – we’re going to trick this evil witch – then a definite end – we have boiled the witch in her own pot and escaped to find freedom away from witches, and (depending on the version you read) parents as well.

In the case of the beanstalk, you could improve this by starting with the ogre robbing Jack, (perhaps through Jack’s own foolishness), Jack wishing he could get revenge, then the beanstalk stuff, then the ogre-slaying. The Ladybird version describes Jack’s thrice robbing the ogre and then throws in that, by the way, the ogre had taken this gold long ago from Jack’s family. No sir. That is not the way to do it. That is like Miss Marple mentioning on page 200 that she had previously spotted the vicar carrying a bloodied axe away from the scene of the crime, but had not thought to say anything until now. Rubbish.

Have your characters state the theme of the story. Be as unsubtle as you like. But darkness is my friend and keeps me safe. No, light is what makes the world go round, and so on. Bash your readers over the head with it so they’re under no illusions about this being anything but a fairy tale.

And finally…

Make stuff up. It needn’t be all princesses and frogs, unless you like that. Some of the most entertaining fairy tales are about ordinary people (usually men, but you can change that). And it’s not usually about finding love either. It’s about survival – a golden goose, an endless pot of porridge, a cat that gives excellent advice. These are what you needed to stand up to The Man in medieval Europe, and they’d be quite handy nowadays too.

So go wild. Put your characters in everyday situations, and give them a problem, and then solve it in an allegorical way. Angela Carter was keen on this. There is a long tradition of stories about interactions with people who turn out to be angels or ghosts. Mix it up. Bring back the talking cat (or axolotl). Bring back seven-league boots (or transporter booths, or hyperspace). Allegory does not need to be set 1000 years ago to work. Have some fun and create a new tradition of tales.

Reading list

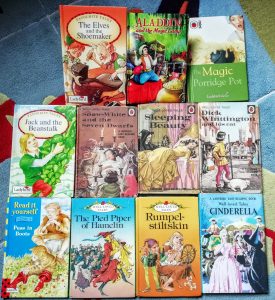

If you want to get your teeth into some traditional European fairy tales before tackling your own, here’s a brief list. I’ll be back with an expansion of this once I’ve delved into non-European ones.

Some of these have further links to tales from outside Europe. I’ll be following those soon.

The Day Boy and the Night Girl by George MacDonald

What’s your favourite fairy tale? Let me know in the comments!

29/08/2018 at 03:25

Simply awesome! I am making note of this and apply your sage advice to some of my own stories-in-process! The creative energies set free! I love it! So tired of “proper literary convention” ! Thank you!

29/08/2018 at 17:50

Thanks! I have a deep suspicion of anything which seems pretentious. That’s what a Lit. degree will do for you. But whatever art you love, cherish. Luckily for Lit professors, I am not representative. 🙂

Thanks for your nice comment!