Life writing can take many forms – but how much truth, and how much fiction, do you put into a novel inspired by real events? What details do you put in, and what can you leave out? How do you handle dialogue and other parts you cannot know? Even if you are working from a pile of historical evidence such as ship’s logs or diaries, how can you be sure that their creators are reliable? How do you make the story of a real life interesting to people other than close relatives? How can you draw from real events a theme or lesson, and give your memoir a structure that actual, messy life cannot have?

Kevin Smith’s book, The Voyage of the Dolphin, appears to

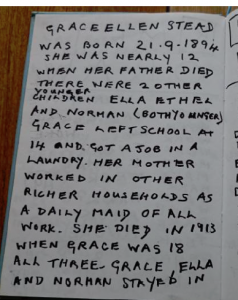

My grandmother hand-wrote her memories when she was 90 – only up to 1946 but we treasure these notes.

be a fictionalised account of a true event in the life of his grandfather: a journey by three Irishmen to the Arctic in 1916, to attempt to recover the bones of a ‘giant’ who perished on an even earlier mission. The voyage takes place against the backdrop of the First World War and the Easter Uprising in Dublin, where the three protagonists are studying at Trinity College. The specifics of life in Dublin at the start of the twentieth century are sharp and precise; the horrors

The specifics of life in Dublin at the start of the twentieth century are sharp and precise; the horrors of a steam and sail powered journey into frozen waters seem straight out of Shackleton’s diaries. And yet as Smith’s tale moves on, the reader becomes ever more suspicious of the veracity of the events. In the final chapters, as the voyagers reach the seas around Greenland, the reader’s belief is stretched to snapping point, until at the end there is only a wistful feeling, a sigh at how wonderful it would be if all this really had happened.

So what is going on with this story inspired by a real life? How can any of that last section be true? (No spoilers: what happens is possible – just – but makes you question everything you know about the Arctic…) It’s an amazing story, though, comical and dark, thrilling and visceral. Would it have been as enthralling without those almost-unbelievable elements?

Many people dream of writing true-life stories – their own, or that of a relative. There may be diaries or letters for inspiration and detail, or just the memories jotted down. My grandmother wrote down the story of her life during the War, laboriously, in giant writing wth a black marker pen, because her eyesight had gone. My cousin scanned them, and now we grandchildren each have a copy. Small details, that none of us knew before, came out in these hand-printed notes.

And yet, even working from direct evidence such as this, ‘truth’ writing poses many challenges, particularly, verifying how much of it really took place. I would be thrilled if my grandfather had written his own memoir of the same period – for contrast! As it stands, we only have our own memories of the stories we were told as children. Over a glass of wine with one of my cousins, we discovered that we had each received a separate set of anecdotes from our grandparents, which did not seem to overlap. I heard mine in the 1970s and 80s, she, much younger, heard these stories in the 1990s. Both of us were learning of events from half a century before. How much was true? How much was misremembered, or embellished after an extra 20 years of retelling?

And … does it matter?

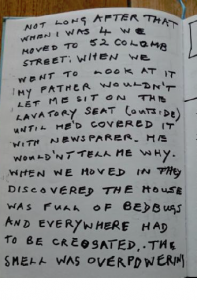

Intimate or weird details make a true life story more compelling. Outside lavatories and bed bugs in the 1930s. Ugh.

It’s possible – likely – that our grandparents’ stories were not quite as thrilling as they seemed. I recall a conversation between my grandparents and some of their friends, about the War. My grandmother Vera said, “Oh, it was a wonderful time, really.” Her friend Joe said, “No, it wasn’t. You were always terrified for your life, afraid a bomb was going to drop on you. It was a terrible time.” And there in that room I realised that the version of the War I’d always believed, a rather romantic version, belonged to my grandmother, and that everyone else had their own experience of events. Joe’s reality seemed more plausible to me. But that too was only his opinion. Which version would you write down in a memoir or novelisation of a real life?

In fact, it doesn’t matter which version you choose, or whether you embellish the facts a little for interest, a little for continuity because chunks of your source material are missing, or a whole lot because it makes a much better story. What matters is that as a writer, you choose consciously how you present the events. Choose the purpose of your life writing and hang your version of events on that:

If it is a personal memoir for your friends and family, you can have a loose structure and no ‘moral’ of the story. Your readers will be familiar with the places and people involved, and they will have their own life’s structure to make sense of the stories you tell.

In a novelisation of an important part of a life, your readers will want a start, middle and end of the story, and a sense of purpose driving towards the outcome. So a memoir of adventures in wartime, might need to be bookended with aspirations growing up which led to becoming a soldier, and the results of the soldier’s experience of battle. Or there might be a structure you can use based around a specific mission, or a specific period such as basic training – something to give a sense of progress through the book.

Some life writing is simply a series of anecdotes, often humorous – but these still need to be tied together by a common theme (lessons learned? time spent in a particular city?) or they will appear as no more than random memories.

For all life writing, look for the most striking, the most unusual or untold aspects of the story. You may not want commercial success with the book, but even your best friends may tire of reading about everyday events. Look for the weird occupations, the strange coincidences and the stories of bedbugs and lavatory seats – see my grandmother’s notes on those, above…

Returning to The Voyage of the Dolphin, it turns out that Smith’s book is not based on real events at all – far from it. It is not a memoir. One of the characters is named after his grandfather. There were no diaries, and crucially, there was no trip to the Arctic. Kevin Smith says he made the whole thing up. He was wondering about his grandfather’s life, and wanted to give him a fantastic alternative life history – and so wrote this thrilling tale of polar exploration and stowaways and indestructible dogs. And I think it’s all the better for the fiction liberally daubed over the fact.

Get the book: The Voyage of the Dolphin, by Kevin Smith

Read more about life writing:

Your Life as Story, Tristine Rainer

Open University Creative Writing coursebook

Have your written a memoir, or are you writing one? What are you putting in, and what are you leaving out? How much truth will you include… and how much fiction? Let me know in the comments!

Leave a Reply - let me know what you think!